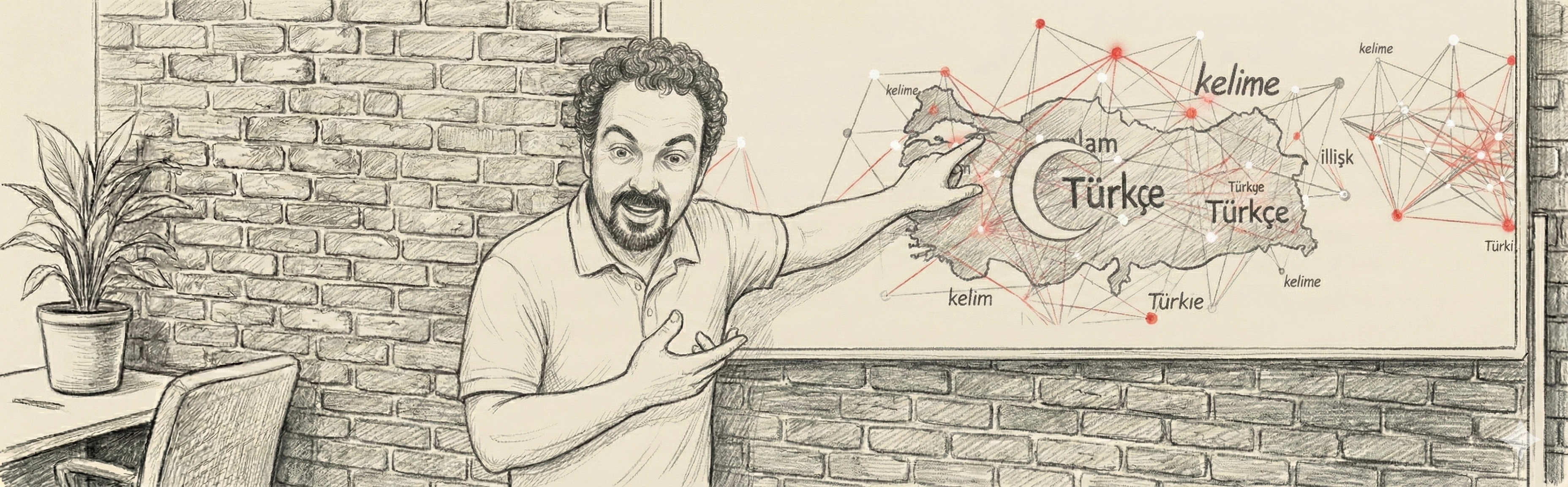

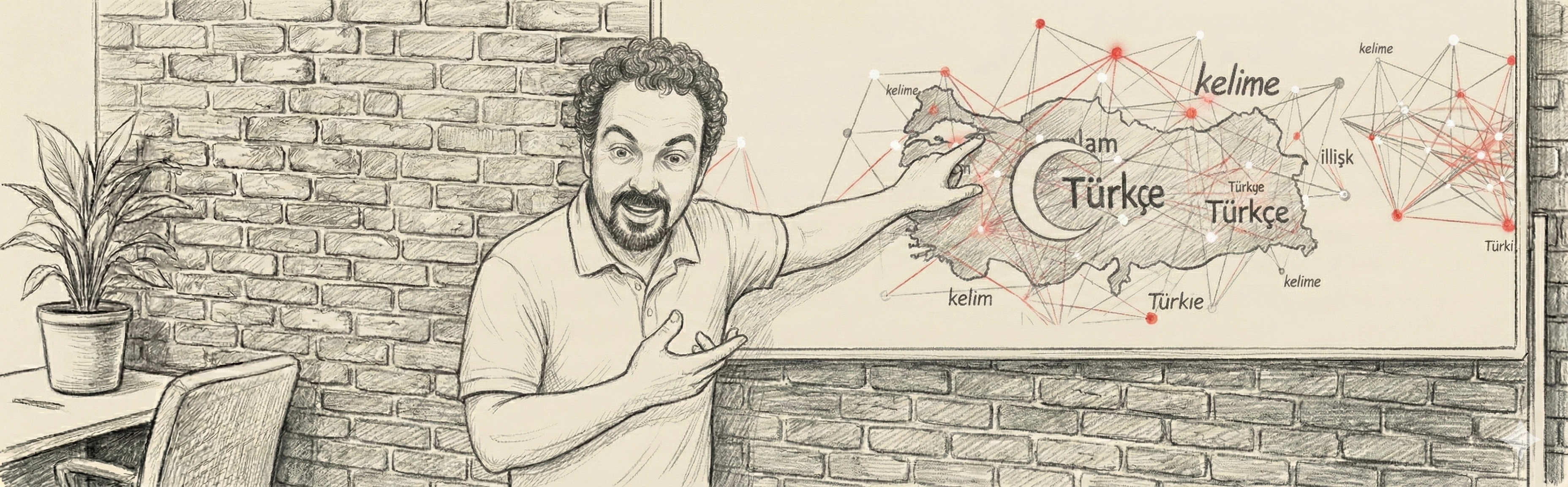

Something happened in 2016 - I found myself drawn into the world of Natural Language Processing. And not just by curiosity, but through a nationally funded research project. Supported by TÜBİTAK, the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (Project No. 215E256), our core team at Çukurova University set out to answer a deceptively simple question:

If a machine is ever to understand Turkish - truly understand it beyond a sequence of letters - shouldn’t it also have its own dictionary?

But not an ordinary dictionary.

A living one.

A dictionary that could update itself — a web of words that continuously evolves.

That vision became the foundation of our project, “The Live Turkish Dictionary Network Design with Weighted Graphs,” which I led from April 2016 to April 2019.

It was completed on schedule, without delay, but the real story lies in how it reshaped our understanding of language itself.

From Words to Networks

Natural Language Processing (NLP) sits at the crossroads of linguistics and artificial intelligence — a field where morphology meets meaning.

But working with Turkish was far from easy. Unlike English, where morphology is relatively light, Turkish is an agglutinative language — each suffix adds a new layer of meaning, blurring the boundary between form and semantics. Finding the true stem of a word can feel like solving a riddle.

We began our journey with these challenges. Our goal was not only to design a morphological analyzer, but also to build an intelligent system capable of automatically discovering semantic relations among words in the dictionary.

Traditional resources such as WordNet had long guided this type of research, yet their manual, expert-based construction was slow and expensive. We dreamed of something more dynamic — a dictionary that could learn from its own patterns.

Designing the Network

At the project’s core was a finite-state morphological analyzer tailored for Turkish morphosyntax.

We implemented Viterbi-based disambiguation to reduce uncertainty and proposed a novel stem discovery algorithm based on recurrence statistics.

Meanwhile, our system began to study thousands of definitions from the TDK Contemporary Turkish Dictionary, gradually recognizing recurring definitional patterns. These patterns revealed hidden links — synonymy, hierarchy, and antonymy — between words.

Using our MentionSense architecture, we transformed these findings into a weighted semantic graph that connected meanings rather than mere entries.

Each edge in this network carried a measurable strength, allowing the system to reason about the closeness of concepts.

In the end, what we built was more than a dictionary — it was a computational model of how meanings resonate across the Turkish language.

What We Learned

Through this network, we discovered that semantic proximity could be quantified using graph-theoretic measures such as PageRank and bidirectional accessibility.

This enabled not only the detection of synonym clusters but also the identification of new lemma candidates.

We even devised a procedure to generate definition suggestions for newly formed or compound words.

In essence, the project showed that Turkish — with all its morphological depth — can be modeled as a weighted, dynamic semantic network.

It revealed that language is not a static tree with roots and branches, but a living web that constantly rebalances itself.

The Team

I was fortunate to lead a passionate and interdisciplinary team:

- Project Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Umut Orhan, Department of Computer Engineering, Çukurova University

- Researcher: Assist. Prof. Dr. B. Tahir Tahiroğlu, Department of Turkish Language and Literature, Çukurova University

- Scholarship Holders: Enis Arslan (PhD Candidate) and Erhan Turan (PhD Candidate), Department of Computer Engineering

Publications

Our work resulted in a number of journal and conference publications, including:

- E. Turan, U. Orhan. Confidence Indexing of Automated Detected Synsets: A Case Study on Contemporary Turkish Dictionary, ACM Transactions on Asian and Low-Resource Language Information Processing, 21(1):18, pp. 1–19, 2021.

- U. Orhan, E. Arslan. Learning Word-Vector Quantization: A Case Study in Morphological Disambiguation, ACM TALLIP, 19(5):72, 2020.

- E. Arslan, U. Orhan. Identification of OOV Words in Turkish Texts, Gaziosmanpaşa Scientific Research Journal, 8(2), 35–48, 2019.

- C. Tulu, U. Orhan, E. Turan. Semantic Relation’s Weight Determination on a Graph-Based WordNet, Gümüşhane University Journal of Science and Technology Institute, 9(2), 67–78, 2018.

- E. Arslan, U. Orhan, B. T. Tahiroğlu. Morphological Disambiguation of Turkish with Free-Order Co-occurrence Statistics, Gümüşhane University Journal of Science and Technology Institute, 9(2), 46–52, 2018.

- C. Tulu, U. Orhan, E. Turan. Determination of Semantic Relation Weights on WordNet, 3rd International Conference on Computational Mathematics and Engineering, 2018.

- E. Turan, U. Orhan, C. Tulu. Using Graph Connectivity Measures for Distance in Semantic Networks, 3rd International Conference on Computational Mathematics and Engineering, 2018.

- E. Arslan, U. Orhan, B. T. Tahiroğlu. Morphological Disambiguation of Turkish with Free-Order Co-occurrence Statistics, INISTA 2018.

- E. Turan, U. Orhan. Building a Turkish Semantic Network and Connecting Synonym Senses Bidirectionally, INISTA 2018.

- C. Tulu, U. Orhan. PageRank-Based Semantic Similarity Measure on a Graph-Based Turkish WordNet, UBMK 2017.

- E. Arslan, U. Orhan. Using Graphs in Construction of a Lemmatization Model for Turkish, IMSEC 2017.

- E. Arslan, U. Orhan. Graph-Based Lemmatization of Turkish Words by Using Morphological Similarity, INISTA 2016.